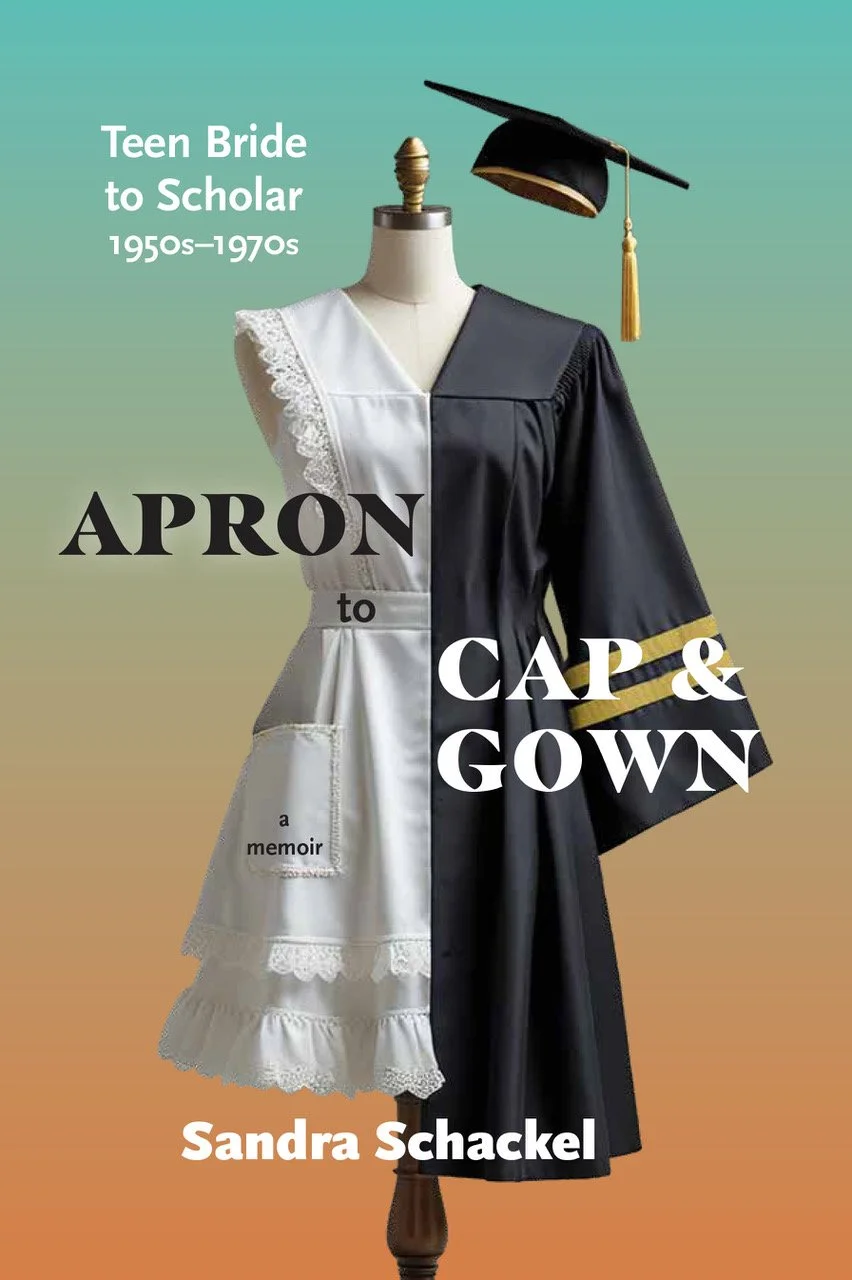

Apron to Cap & Gown: Teen Bride to Scholar, 1950s–1970s

by Sandra Schackel

Burgett Sisters Books

July 29, 2025

Paperback | 176 pages | $19.99

Ebook | $7.99

ISBN print: 979-8-218-49190-1

ISBN ebook: 979-8-218-53852-1

Teen Bride to Scholar | 1950s–1970s

“This book will help any woman take one more look at life and ask: Is this truly where I wanted to go?”

— Jan Salisbury MS, MCC, Executive Coach

Salisbury Consulting

Suddenly, I thought: There must be some other way to be married.

This powerful epiphany underpins Sandra Schackel’s journey from a 1950s teen wife and mom living through second wave feminism—a cultural tremor that would shake up the way women in the 1960s and ’70s would view their lives and identity. The author married her teenage boyfriend and gave birth to their first child before she graduated high school. At a time and an age when youngsters typically dream of their futures, Sandy’s dreams shifted automatically to her husband’s and children’s futures. Like many women, her future—her identity—became obscured. This memoir paints her long and difficult journey toward recovering what was lost and restoring her full sense of self, and the crucial element of her continuing education in helping her succeed.

Available where all fine books are sold.

Praise for Apron to Cap & Gown

“Schackel’s memoir helps us understand how feminism can slowly emerge in a traditional, teenage marriage. We are quickly caught up in the tensions of a restrictive marriage, being a devoted mother, and perpetual setbacks to her pursuit of identity, equitable love, and liberation through education. The writing gives us a vibrant experience of her journey of awareness, pain, and redemption. Chapter titles are songs of the decades, and they capture both the times and her emotional mindset; the author’s inner voice echoes through the music.

With the unembellished perspective of a historian, the memoir then shares how education and feminism shaped a new lens. She confronts herself and her culture, inexorably outgrowing the life created by a 1950s marriage and ultimately achieving her dream of a professorship in history. Sandy’s journey is heroic. This book will help any woman take one more look at life and ask: Is this truly where I wanted to go?”

— Jan Salisbury MS, MCC

Executive Coach, Salisbury Consulting

Apron to Cap & Gown: Teen Bride to Scholar, 1950s–1970s

by Sandra Schackel

Burgett Sisters Books

July 29, 2025

Paperback | 176 pages | $19.99

Ebook | $7.99

ISBN print: 979-8-218-49190-1

ISBN ebook: 979-8-218-53852-1

Available where all fine books are sold.

Apron to Cap & Gown: Excerpts

“How I struggled, argued, acquiesced, resisted, and finally divorced, to create a separate identity for myself, is the basis of this memoir. It was long in coming and wasn’t easy, but it did allow Bill and me to become the people we are today.”

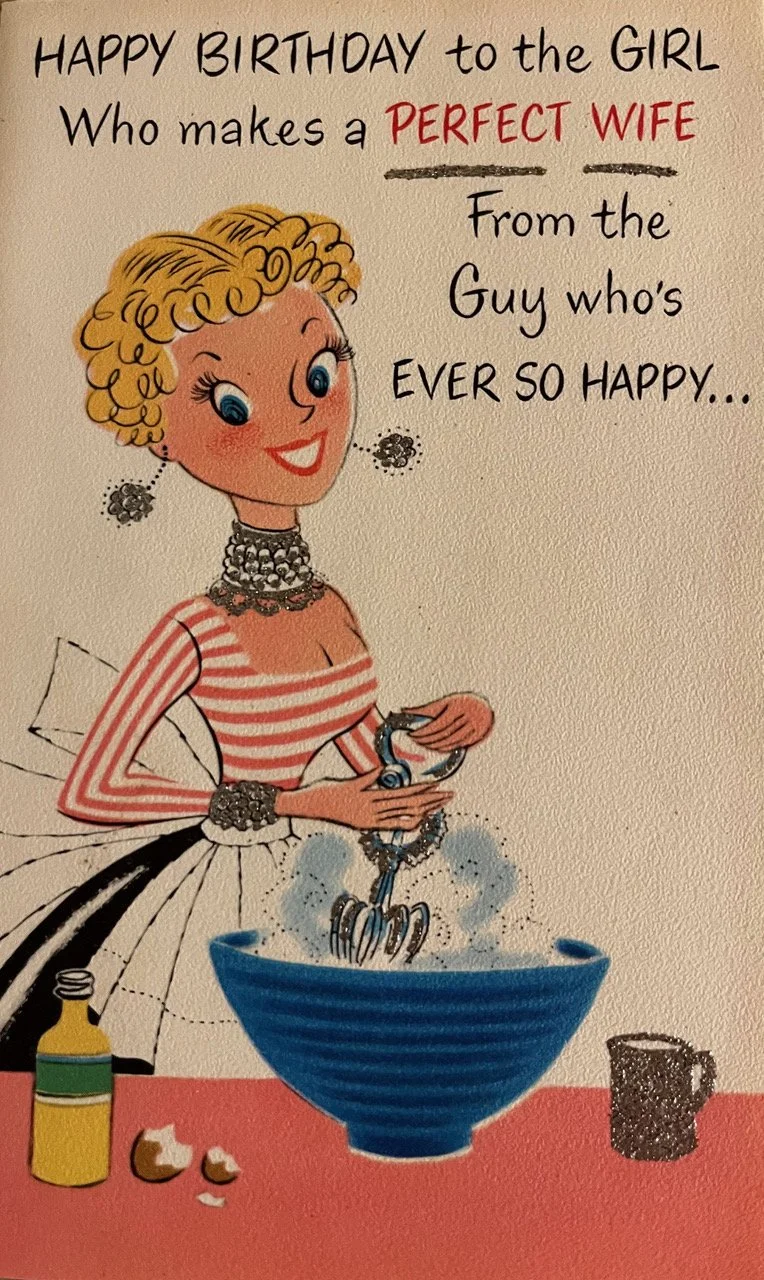

“Like most of our peers, we had had no preparation for sexual activity other than our surging hormones. Social norms had weakened during the war years, and returning soldiers were eager to share their newly acquired sexual freedom with willing girlfriends. Women, however, were caught in a bind. Strict social mores expected ‘good’ girls to hold the line on sexual activity. And when they did succumb to passion outside marriage, shame and stigma usually followed. Girls suffered other repercussions as well.”

“Bill worked construction that summer, and I planted marigolds and put a white picket fence along the front of the trailer. Inside, I happily filled the small cupboards and closets with our wedding gifts and the baby’s items, feeling like I was playing house, my nurturing side showing itself through these domestic tasks. Wasn’t this what I was supposed to be doing, despite being seventeen years old? Over time, this notion of “normal” would come under reappraisal.”

“Two babies in almost two years seemed like the norm in postwar America. I reverted instantly to the traditional family expectation that with marriage came children, pushing the thought of college further into the future. After all, Bill’s intention to become a dentist came before whatever goals I might have. Or so I believed. I was still a long way from questioning the inequities in our marriage that feminists would draw attention to in the 1960s and ’70s.”

“This is who I was at age twenty-five. I could not yet imagine creating an identity of my own outside traditional gender roles. Stephanie Coontz, in A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s, notes that women had few resources to resist the cultural voice that labeled them unnatural if they wished for more than a dependent marital role. I had no idea of how to change my marital status, but I clearly wanted to move beyond it. That latent longing would stay with me and nudge me into imagining myself in college.”

“This was my first encounter with sexism at an academic level. I know now that until I discovered feminism, I had not been aware of the degree to which sexism permeates our lives, a habit that I believe begins within the family. How a dad speaks to his wife and kids makes a powerful imprint on children. Often the result is that sexist language is taken for granted by both those who engage in it and those who hear it. Like most women, I would face more of it, sometimes sly and unobtrusive, but omnipresent throughout American society.”

“A part-time schedule allowed me to continue to play three roles: wife, mother, and student, and I was content with this arrangement. It would gradually get more difficult, but I was still clutching the script I’d been handed in 1958, just squeezing in some ‘me time.’ As wives and mothers know well, carving out time for ourselves means something else usually gets shortchanged. I was determined it would not be my student identity.”

“As Betty Friedan had pointed out a decade earlier in The Feminine Mystique, many college-educated women were beginning to realize that something was missing in their relationships. I didn’t need a diploma to understand that it was equality that was missing in my marriage, and I wasn’t happy with the imbalance. Still, I was uncertain how to do much about it.”

“Although I had not yet read Friedan’s work, instinctively I felt the problem was due to the strict gender role I was limited to as a wife and mother. I wanted an identity beyond that, one that acknowledged my brains, my skills, and my ability to do more than cook and clean. And it surprised me that there seemed to be no space within a traditional union for individuality. I had assumed in my teenage marriage that Bill and I would be equals. But it seems that I had grown up with and internalized an image of marriage that, by the time I was in my thirties, appeared to be a myth. Now I wanted to change the rules, and I was aware that forcing change would be risky. I could not even envision divorce; it was anathema to me.”

“I had become aware that I was in a relationship where my husband had control over my life, or so I believed. I felt stifled and realized Bill had determined the balance of power in our marriage from the beginning. To be fair to him, that was all he knew, the husband as the traditional breadwinner. But I was willing to question and reshape its counterpart, the domestic, stay-at-home wife, so why couldn’t he, or wouldn’t he, also be willing to shift into a more equitable relationship?”

“It may have been serendipity for me that the institution of marriage began to shift in the 1960s and 1970s, from a love-based union to one where personal fulfillment became a valued component. I didn’t stop loving Bill, but my path toward self-expression was underway. Because it wasn’t possible to recognize the breadth or depth of this shift while we were living it, our struggles continued.”

“I wasn’t yet aware of the word patriarchy and how this system determined gender relationships nor the patterns that defined it. But I sensed them. I could look around and see that men were in charge of everything as far as I could tell. Patriarchy meant male domination of the female, and I chafed at that constriction in large and small ways.”

“Gradually, the outer world began to make its way into my narrow life. By the end of the 1960s, what became known as second wave feminism offered new possibilities for healthier male-female relationships. Chafing in the role of wife and mother and wanting more, I felt feminism allowed me to realize that the love-based, traditional marriage was not structurally able to meet my growing needs. Although many women became resigned to their husband’s wishes, I did not. I also felt guilty at not doing so.”

“That insight came to me literally as I sat in Jane Slaughter’s History of Women class in the 1980 spring semester, taking notes as she lectured. Hearing her define patriarchy, rooted in ancient history but still deeply embedded in gender relations worldwide, I nearly gasped out-loud. I was experiencing ‘the click,’ the awareness that this male-driven system is why Bill and I had divorced. With Jane’s words, I suddenly became aware that there was a larger reason for the imbalance in my love-based, male-provider marriage, a universal and all-encompassing system that oppresses women and has a name, patriarchy.”

“Similar instances in my married life suddenly made sense. With that click, I understood that all around me, men were in power everywhere—in marriage, religion, politics, economics, education, business, and more. They were in the pulpit, the ‘corner office,’ and the oval office. The foundation of my being had suddenly shifted.”

“Cracks in the patriarchy slowly developed. The institution of marriage began to shift as the primacy of the patriarchy lessened. The importance of marriage didn’t disappear, but the form changed. The move toward equality between partners that I had longed for with Bill gradually became a reasonable expectation. Younger generations began to embrace these ideas. Older marrieds, not so much.”

“My story may be familiar to many. Or it may be a revelation to some to learn that it is possible to break patriarchal traditions that continue to keep women in unhappy marriages today. I may not have understood the ramifications that my traditional marriage placed on me when I married, but over two decades I gained the courage and the insights to challenge and change what I came to see as limits to my happiness.”